AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize situations where the accumulated change can be found by viewing the region under a rate graph as simple geometric shapes and calculating their areas.’

Understanding accumulated change becomes far easier when a rate graph’s regions form recognizable geometric shapes, allowing students to compute total change using familiar area formulas and clear visual reasoning.

Using Geometry to Find Accumulated Change

This subsubtopic focuses on interpreting the accumulated change of a quantity by identifying when the region under a rate-of-change graph can be decomposed into simple geometric shapes. When this is possible, the accumulation can be determined exactly, without approximation methods such as Riemann sums. The guiding idea is that the area under the rate graph represents total change, and certain graphs allow these areas to be computed precisely using geometry.

Why Geometry Can Be Used

Some rate functions appear graphically in forms that create straight-line boundaries, horizontal segments, or other shapes that correspond to standard geometric regions. When the rate graph is simple enough, these shapes can be recognized directly, and their areas provide the accumulated change over the selected interval.

Common shapes that appear in rate-of-change graphs include:

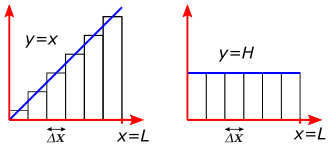

This figure displays two simple functions where the area under each graph is a basic geometric shape: a triangle on the left and a rectangle on the right. The shaded regions represent the accumulated change of the quantity over the interval, computed using the familiar formulas for the area of a triangle and a rectangle. The notation involving and introduces concepts used later in definite integrals and Riemann sums. Source.

Rectangles, often representing a constant rate.

Triangles, frequently arising when a rate increases or decreases linearly.

Trapezoids, appearing when a rate changes linearly between two unequal values.

Semi-circles or quarter-circles, when the rate function describes part of a circular arc.

Combinations of shapes, where separate regions must be computed individually and then summed.

The Meaning of Accumulated Change

The accumulated change of a quantity represents how much the quantity increases or decreases over a given interval due to its rate function. When the rate is positive, the area is interpreted as a positive accumulation; when the rate is negative, the area contributes a negative accumulation. Because this subsubtopic emphasizes geometry, the focus is on regions that can be computed exactly.

A geometric region under a graph is bounded by:

The rate function itself

The x-axis

Vertical lines at the interval endpoints

This creates a closed shape whose area corresponds to net change.

Key Geometric Shapes in Rate Graphs

Identifying geometric shapes allows a direct path to computing exact accumulation. AP students should become fluent in recognizing when a region matches a known shape.

Rectangles

Rectangles arise when the rate is constant across an interval. Their area is found by multiplying height (the rate value) by width (the interval length). Because constant-rate scenarios occur often in applications such as velocity or flow problems, rectangles provide a straightforward method of determining how the quantity changes.

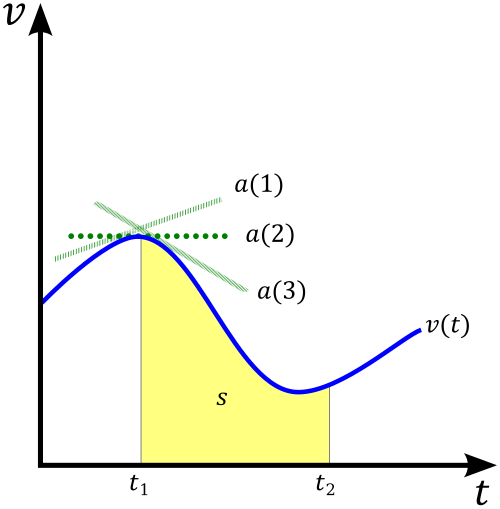

This diagram shows a velocity–time graph, where the area under the curve represents displacement over time. When the graph is piecewise linear or constant, the region breaks into triangles and rectangles, allowing accumulated displacement to be found using simple geometric formulas. The additional labels showing relationships among , , and provide context slightly beyond this subsubtopic but reinforce the interpretation of area as accumulated change. Source.

Triangles

Triangles appear when the rate changes at a constant linear rate, creating a straight-line boundary from one value to another. Their area can be computed using the standard geometric formula, giving a precise measure of accumulation over that portion of the graph.

Trapezoids

Trapezoids emerge when the rate increases or decreases linearly between two unequal endpoint values. This region is especially common because many piecewise-linear graphs consist of connected line segments. Recognizing trapezoids helps students compute accumulated change efficiently without breaking the region into two triangles.

Circular Regions

A rate graph may include arcs shaped like semi-circles or quarter-circles. When this happens, the accumulated change corresponds to the known area formulas for circular regions. Although these appear less frequently than polygons, they are important examples of geometric reasoning applied to integration.

How to Approach a Geometric Accumulation Problem

When students encounter a rate graph, a systematic process helps determine whether geometry provides a suitable approach:

Identify the interval over which accumulated change is being measured.

Visually inspect the graph to determine if the region under the curve on this interval forms a common geometric shape.

Break the region into subregions if necessary, ensuring each subregion corresponds to a known shape.

Compute each area using the appropriate geometric formula.

Assign signs based on whether the region lies above or below the x-axis.

Sum all areas to obtain the total accumulated change.

This structured method ensures accuracy and builds intuition about the relationship between shapes and accumulation.

Importance of Geometric Accumulation in AP Calculus AB

This subsubtopic reinforces a foundational principle: area under a rate graph equals accumulated change. Geometry offers exact results in cases where the integrand behaves in a piecewise-linear or otherwise simple manner. Mastery of this idea helps students interpret real-world scenarios, strengthens conceptual understanding of integration, and prepares them for the later formalism of definite integrals.

When Geometry Applies and When It Does Not

Geometry is ideal when:

The graph consists of straight-line segments.

The graph cleanly forms basic shapes.

The region can be partitioned without ambiguity.

Geometry is unsuitable when:

The function is irregular or curved in a noncircular way.

The region does not correspond to standard shapes.

Precision requires tools beyond basic area formulas.

Recognizing these limitations is part of becoming a flexible and confident calculus student.

Using Signed Areas

Accumulation must reflect positive or negative change. When parts of the graph lie below the x-axis, those areas must be treated as negative. This allows the geometric approach to match the conceptual framework of integration, reinforcing the idea that a rate can decrease a quantity as well as increase it.

Connecting Geometry to Future Concepts

Although this subsubtopic emphasizes geometry, it prepares students for the more formal definition of the definite integral. Understanding that accumulated change corresponds to area under the curve provides an essential stepping stone toward Riemann sums and ultimately the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

FAQ

Look for straight-line boundaries, horizontal segments, or smooth arcs that match standard geometric shapes. If the graph consists of piecewise linear segments, it usually indicates triangles, rectangles, or trapeziums.

If the curve bends irregularly or changes slope multiple times in a non-linear way, geometry is unlikely to give an exact result, and numerical methods would typically be required.

Break the interval into smaller sections. Use geometric formulas where the graph forms clear shapes and leave the remaining portion for alternative methods if needed.

However, in AP contexts, questions designed for geometric solutions generally ensure all regions fit standard shapes, so mixed techniques are rarely required.

Graphical representations in exam questions often simplify real behaviour, using approximated straight-line segments. These approximations create geometric shapes that still give meaningful accumulated change.

This approach helps build intuition about how rates relate to area before introducing more formal integration tools.

Identify whether the region lies above or below the horizontal axis.

• Above the axis: treat the area as positive.

• Below the axis: treat the area as negative.

If the graph crosses the axis, split the interval at the crossing point and compute each area separately before combining them with appropriate signs.

Yes, as long as the curve truly forms a known geometric arc (such as a semicircle or quarter-circle). Exam diagrams sometimes include these to test recognition of less common shapes.

If the curve approximates a circular shape but is not exact, geometric formulas should not be used, as the resulting accumulated change would be inaccurate.

Practice Questions

A rate-of-change graph consists of a straight-line segment from x = 0 to x = 4, increasing linearly from a rate of 0 to a rate of 6. Using geometric reasoning only, determine the accumulated change of the quantity over this interval.

(1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Recognises that the region is a triangle.

• 1 mark: Uses the area of a triangle formula or correctly sets up base and height.

• 1 mark: Correct accumulated change = 12 units.

(Base = 4, height = 6, so area = 1/2 × 4 × 6 = 12.)

Total: 3 marks

A function r(t) gives the rate at which water enters a tank. The graph of r(t) consists of two geometric regions:

• From t = 0 to t = 3, the graph is a horizontal line at r(t) = 5.

• From t = 3 to t = 7, the graph decreases linearly from r(t) = 5 at t = 3 to r(t) = 1 at t = 7.

(a) Identify the geometric shapes formed under the graph on each interval.

(b) Compute the area of each region using geometric formulas.

(c) Hence determine the total accumulated volume of water entering the tank over 0 ≤ t ≤ 7.

(4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Identifies the first region (0 to 3) as a rectangle.

• 1 mark: Identifies the second region (3 to 7) as a trapezium (or equivalently a triangle plus a rectangle).

(b)

• 1 mark: Correct area of the rectangle = 15 units (base 3, height 5).

• 1 mark: Correct area of the trapezium = 12 units (parallel sides 5 and 1, width 4).

(Allow equivalent reasoning using triangle and rectangle components.)

(c)

• 1 mark: Correct total accumulated volume = 27 units.

• 1 mark: Clear reasoning showing sum of geometric areas.

Total: 6 marks